Characteristics of Sotos syndrome

Epidemiological characteristics

In Japan, it is estimated that there is one patient in every 12,000 people , and more than 800 cases have been confirmed to date, with no gender predilection. Prognosis is said to be affected by diseases of the heart, kidneys, and nervous system, but there is no impact on life expectancy. However, since only a little less than 60 years have passed since Sotos syndrome was discovered, long-term follow-up is desired.

Physical characteristics

Sotos syndrome is a genetic disorder first reported in 1964 and is characterized by excessive prenatal and postnatal growth, a large and elongated (dolichocephalic) head, distinctive facial morphology, and a non-progressive neurological disorder accompanied by intellectual disability . Approximately 75-85% of patients also have advanced bone age.

The main clinical finding is prenatal and postnatal overgrowth. Growth velocity is particularly excessive during the first 3-4 years of life, progressing at a normal rate thereafter. The average height is usually 2-3 years higher than childhood peers, and although weight is usually appropriate for height, children are characterized by being on average 2-4 years taller than their age during childhood . Some patients have been known to exceed the average adult height.

The craniofacial morphology is the most distinctive feature, and 96% of patients may have a distinctive head shape with a prominent forehead and a receding hairline, dolichocephaly, wide eyes (hyposteosis), downward sloping and folds of the eyelids (eyelid features), a high palate, a pointed chin, and an elongated face. The typical facial features are most evident during childhood. As the child grows, the chin becomes more prominent and may become square in shape. In adults, the craniofacial features are less pronounced, but a prominent chin, dolicocephaly, and a receding hairline (frontal bossing) may remain.

Symptoms of Sotos syndrome

Neurological symptoms

Central nervous system symptoms are common in this disorder. Delays in achievement of developmental, walking, speaking, and especially speech milestones are almost always present, as well as clumsiness (60-80%), as well as hypotonia (low muscle tone) and joint laxity. Intellectual disability is present in 80-85% of patients, with an average IQ of 72, ranging from 40 to borderline mild intellectual disability. Intelligence is normal in 15-20% of patients. Seizures may occur in 30% of affected individuals.

Symptoms in other areas

Newborns often present with jaundice, feeding difficulties, and hypotonia. Approximately 8-35% of children with Sotos syndrome have cardiac abnormalities, but these are usually not severe. Genital and/or urinary system abnormalities are present in approximately 20% of patients. Other findings associated with Sotos syndrome include conductive hearing loss, which may be related to increased frequency of upper respiratory tract infections, eye abnormalities such as strabismus, and skeletal abnormalities. Curvature of the spine (scoliosis) is present in approximately 40% of patients, but is usually not severe enough to require bracing or surgery. Approximately 2.2-3.9% of patients may develop tumors, such as sacrococcygeal teratomas, neuroblastomas, presacral ganglioneuromas, and acute lymphoblastic leukemia.

Affected infants and children usually have delays in achieving certain developmental milestones (e.g., sitting, crawling, walking, etc.). For example, they may not begin to walk until approximately 15-17 months of age. Affected children may have difficulty performing certain tasks that require coordination (e.g., riding a bike or playing sports), fine motor skills (e.g., the ability to grasp small objects), and may exhibit abnormal movement disorders. In addition, there is typically a delay in acquiring language skills, and affected children are often not able to speak until around 2-3 years of age .

Causes of Sotos syndrome

Sotos syndrome is known to be caused by mutations (abnormalities) in the NSD1 (nuclear receptor-binding SET domain protein 1) gene. Mutations in this gene have been identified in approximately 90% of patients. In addition, the identification of NSD1 mutations that cause Sotos syndrome was first established in the Japanese population, and it was found that haploinsufficiency of the NSD1 gene is present in many patients with a clinical diagnosis of Sotos syndrome. Specifically, a partial deletion of the entire autosomal region of the NSD1 gene at 5q35 has been observed in the Japanese population. On the other hand, in foreigners, intragenic mutations in the NSD1 gene are the most common cause, accounting for approximately 83% of cases. The remaining patients who meet the clinical criteria but do not have NSD1 mutations are diagnosed with Sotos-like or Sotos syndrome-2. Studies of Sotos-like patients (those without NSD1 abnormalities) have identified mutations in the NFIX gene (nuclear factor type I,X) in five patients with Sotos syndrome, and loss-of-function mutations in the APC2 (adenomatous polyposis coli 2) gene have been reported in two patients with Sotos neurological features. Studies of NSD1-positive individuals have examined specific genotype-phenotype correlations associated with various NSD1 abnormalities; namely, patients with the 5.q.35 autosomal partial deletion of the NSD1 gene have less pronounced overgrowth and more severe intellectual disability compared to patients with mutations in the same gene. Because genetic abnormalities are absent in approximately 10% of cases, clinical evaluation remains an important part of the diagnostic process.

The syndrome includes intellectual disability, abnormal brain structure, and typical facial features, but does not include other features such as bone or cardiac abnormalities. The APC2 gene is specifically expressed in the nervous system and is one of the important downstream genes of NSD1. In other words, mutations in the NSD1 gene affect the APC2 gene and cause neurological abnormalities.

Sotos syndrome is an autosomal dominant condition that occurs when only one copy of an abnormal variant of a gene is needed to cause a particular disease. The abnormal variant gene may be inherited from a parent, or a mutated (changed) gene may be causative in an affected individual. The risk of passing the abnormal variant gene from an affected parent to their child is 50% with each pregnancy; these risks are the same for both sexes.

Most people with Sotos syndrome have NSD1 mutations as a result of new mutations not inherited from a parent. If a parent is unaffected, the risk of the next child developing the syndrome is very low (less than 1%). Symptoms of Sotos syndrome vary from person to person, even if they have the same NSD1 gene mutation.

However, Sotos syndrome is also considered to be an autosomal recessive condition. Recessive genetic disorders occur when an individual inherits an abnormal variant of a gene from both parents. When an individual inherits one normal gene and one abnormal variant for the disease, they become a carrier of the disease and usually do not show symptoms. If both parents who are carriers inherit the abnormal variant, the child has a 25% risk of being affected with each pregnancy. The risk of having a child who is also a carrier is 50% with each pregnancy. A child has a 25% chance of inheriting normal genes from both parents, and these risks are the same for boys and girls.

Diagnosis of Sotos syndrome

There are no biochemical markers for Sotos syndrome. Therefore, the diagnosis is made on clinical grounds. The most characteristic clinical features are craniofacial morphology, excessive growth, and developmental delay . Craniofacial morphology is the most characteristic and is rarely absent (approximately 1%). Children and adolescents may not be overly tall, and 10-15% of patients may not have developmental delay. Additionally, advanced bone age is seen in 76-86% of patients, but has been found to be useful but not specific. Brain abnormalities, such as hydrocephalus, are seen in 60-80% of patients, but are not diagnostic and are considered nonspecific.

Genetic diagnosis is performed by simple and reliable methods such as FISH (fluorescence in situ hybridization) analysis to detect whole autosomal partial deletions or MLPA (multiple ligation-dependent probe amplification) to detect whole autosomal partial deletions at chromosome 5q35 and partial NSD1 gene deletions. DNA analysis by genomic sequencing can also determine the specific NSD1 gene mutation. As mentioned above, it is suggested that genetic testing for mutations in the NFIX and APC2 genes should also be performed in patients without NSD1 gene mutations.

Diagnostic criteria for Sotos syndrome in Japan

A diagnosis is confirmed when a patient has 1 to 3 of the main clinical symptoms shown below and either a point mutation in the causative gene (NSD1 gene, etc.) or a deletion in the long arm of chromosome 5, which includes NSD1. As mentioned above, there are cases where no mutation or deletion is found, and a clinical diagnosis of Sotos syndrome is made when all of the following symptoms 1 to 4 are met.

Ⅰ.主要臨床症状

- 1. Macrocephaly in infancy and early childhood (≧2 SD)

- 2. Overgrowth in infancy and early childhood (≥2 SD)

- 3. Characteristic appearance including a large and dolichocephalic head, large limbs, prominent forehead and jaw, high palate, downward-slanting palpebral fissures, and hypertelorism

- 4. Mental Retardation

*SD (Standard Deviation) is an abbreviation for standard deviation, and 2SD indicates the range that contains approximately 95% of the data around the average value.

Severity classification of Sotos syndrome in Japan

The severity is classified according to the following criteria:

1. Pediatric cases (under 18 years old)

The severity of the condition is the same as that of specific chronic childhood diseases.

2. Adult cases

This program is for people who fall under any of the following categories 1) to 4).

1) Intractable epilepsy: A condition in which seizures have not been suppressed for more than a year, despite treatment for more than two years with sufficient doses of two or more major antiepileptic drugs, either alone or in combination, and which interferes with daily life (defined by the Japanese Society of Neurology).

2) Patients with congenital heart disease who are classified as Class II or higher in the NYHA classification even after drug therapy or surgery. Example: Class II (Class II: Mild to moderate restrictions on physical activity. No symptoms at rest or during light exertion. Relatively intense daily exertion (e.g., climbing stairs, walking uphill, etc.) causes fatigue, palpitations, dyspnea, fainting, or angina (chest pain).)

3) In cases where a tracheotomy has been performed, parenteral nutrition is being administered (tube feeding, total parenteral nutrition, etc.), or artificial respirator is being used.

4) If accompanied by renal failure (if the CKD severity classification heat map is in the red area).

Treatment and testing for Sotos syndrome

Treatment of Sotos syndrome targets the specific symptoms evident in each individual patient. Due to the variety of symptoms, treatment may require the coordinated intervention of a team of specialists, including pediatricians, pediatric endocrinologists, geneticists, neurologists, surgeons, orthopedic surgeons, ophthalmologists, physiotherapists, and other medical professionals to systematically and comprehensively plan treatment.

If a child is diagnosed with Sotos syndrome, a cardiac examination and ultrasound should be performed and an appropriate specialist should be consulted if abnormalities are identified. Children with Sotos syndrome should also have a thorough medical check-up every 1-2 years, including a back exam for scoliosis, eye exams, blood pressure measurement, and an evaluation of speech skills.

Clinical evaluation should be performed early and on an ongoing basis to help identify the presence and severity of developmental delay, psychomotor retardation, or intellectual disability. Such evaluation and early intervention have been shown to be helpful in ensuring that appropriate measures are taken to help patients reach their fullest treatable potential. Treatments that may benefit affected children include social support, physical therapy, occupational therapy, speech therapy, and adaptive physical education.

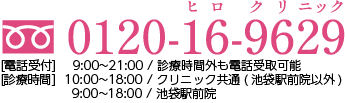

Article Editorial Supervisor

Dr. Shun Mizuta

Head Doctor, Hiro Clinic NIPT Okayama

Board Certified Pediatrician, Japan Pediatric Society

As a pediatrician, he has been engaged in community medicine in Okayama Prefecture for nearly 30 years.

Currently, he is working to educate the community about NIPT as the Head Doctor of Hiro Clinic NIPT Okayama, utilizing his experience as a pediatrician.

Brief History

1988 – Graduated from Kawasaki Medical University

1990 – Clinical Assistant, Kawasaki Medical University, Department of Pediatrics

1992 – Department of Pediatric Neurology, Okayama University Hospital

1993 – Head of the First Department of Pediatrics, Ihara Municipal Hospital, Ihara City

1996 – Mizuta Kodomo Hospital

Qualifications

Board Certified Pediatrician

中文

中文